Priyanka, though an ‘outsider’ in Bollywood- she is one of the lucky few with some privilege – she has her ‘Miss World’ title to bank on and parents to fall back on.

There are two conflicting opinions on Priyanka Chopra- former Miss World and Actor adding the title “Jonas” to her name- and thus becoming Priyanka Chopra Jonas – after her big fat Indian wedding.

One – it is her choice; Two – as one of the role model for/of women, why did she do that? Why should she take/ add her husband’s title to her name?

Priyanka Chopra is a given name – yeah, she did not choose it (did she?). But to add Jonas is her choice – a decision made by her (didn’t she?).

I happen to be among the first group. My first re-action on the question – what do you say about Priyanka adding the ‘Jonas’ title, was – “it’s her choice”. She is an adult with her own mind, educated, well exposed to the outside world, opinionated, a former beauty queen and one of the most popular face in the world.

Priyanka is a woman of privilege and power

My observation is that, in Priyanka’s case, unlike majority of, say for instance Indian women, who do not have a ‘choice” – who were assumed or automatically given their husband’s title after marriage (yes, without asking them!) – Priyanka’s case is not so.

Classic case – you go to the hospital – they ask your name – obviously your marital status – the doctor without a blink writes your name (patient’s name) with the husband’s title, right? Or you go to any institutions or any register counter – a woman’s name and title (surname or second name) always goes with the husband’s – unless you tell them or give in writing that “this is my name”- saying that you did not take/ add his title.

Chopra – I believe- is someone who knows what she is doing- surely she is not – subtlety or unknowingly – forced or coerced to add “Jonas” in her title.

Never miss real stories from India's women.

An intelligent woman who understands the reality of her profession

Chopra is one of my favorite actor. Especially after watching her in Fashion (a movie that I saw more than once). Since then somehow I have been following her movies, and of late her talks, discussion and chat shows. I have found her very talented and versatile. Chopra is smart and intelligent. She is ambitious and doesn’t mind saying that. I find her courageous and outspoken – but knows where to draw the line.

On asked if she is irritated by the paparazzi in one of her interviews she said “aren’t we in this business to be photograph?” That was a good one. She is realistic.

All the more that her philanthropy and talk of women empowerment, girl child, had really touched million hearts and she is worth listening.

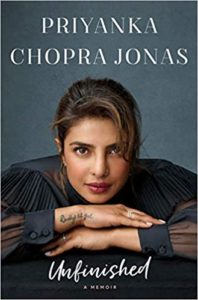

Priyanka’s memoir Unfinished

Her memoir- Unfinished is just as entertaining as her. A story of her evolution from a ‘middle class’ (a term she often used) to a global phenomenon. The memoir is quite revealing – in that she tells about her fears- her inhibitions- of making peace with her inner self.

In short Priyanka is a quick learner and how she moves on in her life is remarkable.

Though she did not write much about the ‘inside’ of Bollywood – or the Hindi film industry as she puts it, her recollection of her beginner days were creepy and un-friendly. She was advised to get a boob job, fix her jaw, and a little more cushioning on the butt. Of course, Priyanka did not follow the unsolicited advice, obviously ! Priyanka – a new comer –step out of a project that requires her to “show her chaddiyan” in a song sequence. Priyanka mentioned that on being removed from a role just because an actor wants his girlfriend to be cast is such a humiliating experience. And one can imagine what Priyanka or other crew would feel, waiting for the male lead –who comes in at his own sweet time for shooting. This are few of the things she mentions; of course there would be many incidents and events of experience. But these are enough as evidence of what women actors go through in the film industry in India. Moreover, her mention of the ‘un-equal wage’ in the film industry is worth a note.

All this, comparatively are just a tip of the ice berg, as many have also stated.

Priyanka, though an ‘outsider’ in Bollywood- she is one of the lucky few. She has her ‘Miss World’ title to bank on and parents to fall back on. It is a known fact that many female actors could not survive in the industry.

Priyanka, though an ‘outsider’ in Bollywood- she is one of the lucky few. She has her ‘Miss World’ title to bank on and parents to fall back on. It is a known fact that many female actors could not survive in the industry.

Priyanka is a survivor.

Reading her memoir, it can be said that Priyanka strongly holds on to her ‘Indian-ness’. She stated that she is a product of “tradition and modern India”. She seems to jealously guard this.

But is there more to it than meets the eye from the book?

It is said that celebrity memoirs are not the ‘tell-all’ story. Indeed, Priyanka’s story is not ‘finished’. I believe there is still some unfished story about the ‘Chopra-Jonas’ product. How or why she decided to take the title. Maybe a sequence of the memoir – part 2? I believe fans are eager to know.